Power and Sacrifice

In an earlier post this year, I reiterated a basic dynamic in our social life that I am not the first to identify, but that I think generally holds: that conservatives have significant political power but feel embattled and resentful due to progressives’ cultural power, and progressives have significant cultural power, but feel embattled and resentful due to conservatives’ political power. That basic assessment requires significant explanation and caveats, but there’s a core truth to it that is helpful as you look out and try to make sense of our politics and broader public life. For a deeper read on this dynamic, I really appreciate how Osita Nwanevu explored this dynamic from a left-wing perspective in an essay last year.

I thought about this again when I saw this tweet:

Now there is a generous reading of this tweet in which you read it as a sloppy, personalized way to convey what has now become a conventional argument: the Senate is an undemocratic institution because it essentially affords certain people more of a say based on the state where they live. And I’m sure that’s exactly what this tweeter (I don’t know him) intended to convey. But the tweet did not make a straightforward, merely analytical point, but instead was personalized in such a way that it read like a tweet-sized summary of Christopher Lasch’s Revolt of the Elites. The fact that our economy, that modern life itself, has developed in such a way that one could live in Montgomery County, MD (one of the wealthiest counties in America), LA, Chicago, San Francisco and Boston actually strengthens, in my view, the rationale for having a Senate where seats are apportioned in the way that they are and have been. Another way of reading this tweet is: places like Wyoming don’t deserve the political power they have, because they lack the economic power we have.

Much of our politics and social life today is driven by a deep resentment that the power we have is not sufficient to buffer ourselves from the influence of different kinds of power, nor is it sufficient to dictate what happens outside of our immediate influence. In short, we are resentful of pluralism. We are resentful that the power that we do have does not enable us to always control and coerce.

We seek to justify this resentment by building up narratives about why the form of power we have is superior, why our particular group is superior, and why, in fact, our interests and perspective should dictate things. Business and tech are the sectors that actually “do things” and “create value.” Culture cultivates and reflects people’s affections and deepest desires. Politics is a realm which has the power to legitimize, or seem to legitimize, certain accounts of what is just and unjust, right and wrong, via the acquisition and deployment of power.

We marshal resources to insulate our power base from interference from others, and seek to use our power to impose what happens in other sectors. Social conservatives use their political power to push back against the cultural power of progressives. Business leaders use culture to boost their profits, and use their financial power to stave off regulation or other undesirable legislation. Progressives use their cultural power to try to dominate the political discourse and pressure corporations.

One could envision a pluralistic society that could work relatively well with various demographics having their own sectors of influence which act as a check on others. It would be an antagonistic society, but it would allow everyone to feel like they have a place; that they are “in the game.”

Of course, what we have now is not a society in which everyone has a power base, but where there is an elite class of people in various sectors that wield power while leaving vast swaths of people unrepresented. We also see how the system we have raises animosity within sectors. This is why the Ahmari-French dispute took up so much oxygen, even though it was between two conservatives. This is why Democrats’ animosity toward Sen. Manchin is reaching fever pitch, particularly among cultural elites. We would be able to do exactly what we want to do if only it wasn’t for these dissenters, these people who do not get it. This is why you see growing conflict between cultural gatekeepers (see: Netflix) and the creative class. It’s part of why Fox News is so reviled: it’s the crack in the armor. When this environment is toxic, it leads people to do extraordinarily harmful things when their power base is threatened. Social conservatives, for instance, look out and think: if we don’t have political power, what do we have? It becomes an existential crisis. This is the very dynamic which Trump exploited so explicitly.

My interest though is not in making this current system of an equilibrium of self-interested, self-serving power centers sustainable, but in developing an imagination for what we might do with the power we have, and how we might think about the power we have. The problem is not just that we do not do what is right, but that we gain such a sense of superiority and animosity when we do what we think is right. It did not take long for the self-congratulatory moralism of the vaccinated and the locked-down to turn into animosity toward those who would not or could not act in the same way. The language so often slips from that which is oriented toward the public good, to if it weren’t for you and people like you, my sacrifices, my good behavior, would have earned me better than what I have now. How quickly COVID moralism has turned punitive.

What we need is a vision for right action that is justified even in the face of loss. We need a source of conviction that is strong enough to sustain that vision.

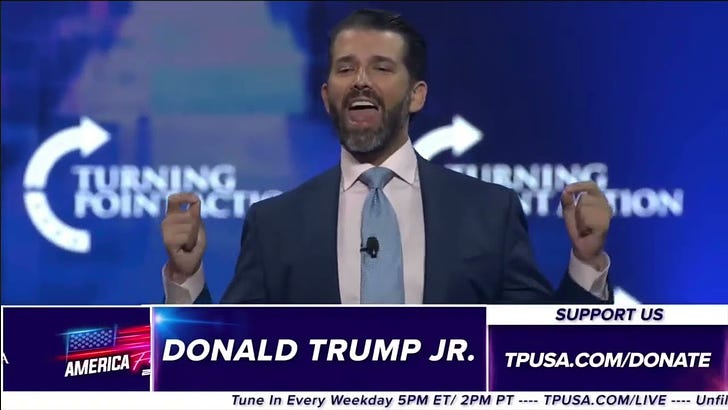

Donald Trump Jr., and his father, for instance, continue to work to undermine such a vision. Watch Donald Trump Jr. at TPUSA this past week tell an audience that while he “gets the biblical reference” to “turn another cheek,” it has “gotten us nothing.”

In a healthy pluralistic society, we will resist the urge to control and coerce using whatever power is at our disposal. We will pursue and accept, as Andy Crouch has suggested, both authority and vulnerability.

Praxis, the organization where Andy serves, talks about this vision in terms of the Redemptive Edge. Praxis describes the Redemptive Edge as “creative restoration through sacrifice.” It includes, but goes beyond, the ethical. If the ethical reduces hard coercion, the Redemptive Edge puts a full-court press on control and coercion of all kinds. What would it look like if the sectors of society in which we found we had real power were viewed as forums to pursue “creative restoration through sacrifice” rather than coercion and control?

A healthy pluralism requires a respect for others’ will. A healthy pluralism requires that we not always seek to override others’ interests when we have the power to do so, but that we are prepared to sacrifice maximal advantage for the good of the whole, even those we do not understand.

These are provisional thoughts, but ideas that I expect will guide much of my thinking in 2022. What does strategic sacrifice look like in public life that conveys care beyond self-interest and personal benefit? How might such an approach, in public, affect the problems of distrust and aversion that so dominate public life today? And what resources are available to us that might support such an approach?

If you liked this post and would like to support our work, we have a holiday special where you will get 50% off our annual subscription ($25 for an entire year of subscriber-only posts!). Buy it for yourself, or as a last-minute gift. Your support fuels our work every single week.