Y’all have Yang on the brain. Andrew Yang, the presidential candidate, keeps coming up in my conversations. Subscribers to this newsletter have asked about him. People at my events ask about him. I have literally been stopped on the street by someone who wanted to ask me about Andrew Yang. So I don’t have a specific question to tag this too, let’s count this as a QOTW (Question of the Week) because this is the direct result of a number of questions I’ve received that all now form in my mind as one general question: “What do you think of Andrew Yang?” (As a reminder, all paid subscribers are invited to ask a question that we’ll answer in this newsletter by emailing RHNQuestions@gmail.com.) I offer a few thoughts here, but I’d encourage subscribers to comment on this page or anyone can email me directly with your thoughts about the candidate.

First, though, a very quick heads up: watch out for the Trump Administration picking up its criticism of the Federal Reserve to shift blame for bad economic news. The Fed is the perfect kind of bogeyman for a populist who won’t take responsibility for anything that goes wrong.

OK, back to Yang.

Who is Andrew Yang?

Andrew Yang is a businessman and entrepreneur. He has degrees in political science and economics from Brown and a law degree from Columbia University. After selling an education company he founded, he created Venture, “an organization that helps entrepreneurs create jobs in cities like Baltimore, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland.” Read more of his bio, in his own words, on his website.

What does Yang stand for?

Yang’s principal policy proposal is the Universal Basic Income, which would effectively give every adult citizen in America $1000/month. He calls it the Freedom Dividend. Yang also supports Medicare for All and what he called “Human-centered capitalism.”

There are about a hundred other policy proposals on Yang’s website that range from paid family leave to extending daylight savings time all year.

Why is Yang attractive to a significant cohort of voters?

As with any presidential candidate who attains even marginal success, there is no single reason for that success. There are plenty of ideas about Yang’s appeal, including the idea that he’s attracting disaffected white guys who are progressive on social issues, but appreciate that he has “come out against identity politics, which as a young white man I feel is putting us down at the lowest point, and for him to come out against that means a lot to me,” as one young man told Emily Witt for her fantastic New Yorker profile of Yang. Others point to the payout promised by his Freedom Dividend.

I want to pull out a few reasons why I believe Andrew Yang is attractive to a significant number of Americans right now.

Yang is not so invested in partisanship, and his approach is not shaped by a partisan imagination.

Look at Andrew Yang’s policy page and you’ll find policies that range from, yes, a proposal for Medicare for All, but also a range of policies that don’t seem to speak to any political interest at all. There are ideas there that don’t seem to have any political purpose at all.

In most of the major talks I’ve given over the last several years, I’ve included a section along these lines:

Political campaigns understand and feed into this emotional pull of politics. Increasingly, political messages are not about policies; instead, the policies proposed on the campaign trail are about sending a message and propping up a desired narrative. Our politics is both driven by and guiding our emotions.

The influence of political tactics is not confined to campaign dynamics. It affects how we are formed as people. Political polarization is at an all-time high. Instead of our values influencing our politics, our political circumstances are shaping our values. As partisans, we explain away the flaws of the candidate we support, and buy nearly any outlandish theory about the candidate we oppose. We even change what we believe to fit the moment.

It’s amazing to read some of the reporting and analysis of this aspect of Yang’s campaign. Political journalists, who have rightly learned that most campaigns think of policy as a tool for building a political coalition, look at Yang’s approach as a novelty. Why on earth is he highlighting daylight savings time on a presidential campaign? What voters will turnout because of that policy? Do voters really hate the penny that much?

I think a certain kind of voter looks at Yang’s website, and hears Yang talk, and thinks that here’s a guy who is not trying to manipulate them. $1000 monthly government checks aside, Yang is someone who just has some ideas about how to make the nation better. He’s not trying to piecemeal his way to 50%+1 or 270 electoral votes. He’s not proposing these policies because they poll well or excite the right kinds of people.

Even on an issue like abortion, Yang’s website contains little of the rhetoric typically found on Democratic campaign websites about how evil anti-choice Republicans are and how people who disagree want to “drag women back” to the 1950s. In fact, though there might be some examples I missed, on a brief search of his website, I could not find an example of Yang using Republicans as a foil on his policy pages. There are references to counter-arguments that are made to policies like his Freedom Dividend. On the abortion page, he does reference “legislators who have no background on the procedure or even the basics of medicine.” But Yang is not constantly looking to get a partisan jab in, or frame his ideas in light of the framework of partisan politics. (In this way, I couldn’t help but be reminded of how Barack Obama would invoke the way his U.S. Senate campaign website discussed the issue.)

Instead, Yang’s policy pages rather attractively and compellingly lay out his policy ideas by starting with a description of the policy, then the problems it seeks to solve, the principles that guide the policy approach, the goal of the proposed policy and then a succinct commitment Yang has made on how he’ll address the issue as president. It’s the kind of thing that is meant to make your nod your head, and mutter to yourself well, that makes sense.

In a time when neither of our political parties poll particularly well, Yang’s relative disengagement from party politics and partisan thinking seems refreshing, authentic and more trustworthy.

Yang is a structuralist, who wants to divest the presidency of its massive cultural functions and influence.

The reasons for the success of Yang and Williamson are shared in some cases, including what was covered above and what will be discussed below, but they differ in one obvious, central way. Williamson has identified America’s problems as primarily spiritual, and her presidency (stay with me) as an opportunity for spiritual healing. Williamson will lead a revolution of love through the force of her personality and her insight into the human condition. She has declared in debates, on stage with Yang and Elizabeth Warren along with others, that policy plans won’t defeat Donald Trump and won’t fix what ails the nation. The presidency for Williamson is the pinnacle of moral and cultural leadership.

Yang, on the other hand, literally has a policy proposal to strip away many of the ceremonial functions that the president has typically held. He is frequently referred to as a technocrat for good reason, and is running a policy-driven campaign. As The Atlantic’s Edward-Isaac Dovere reports in his recent profile of Yang, he has identified many problems and they are big problems. He uses terms like “dystopia” to discuss America’s potential future, and highlights deeply structural issues developing in technology, science, the economy and other areas. For some, his analysis puts some words and ideas to a feeling of despair that feels unutterable or laughable.

Read this exchange from Dovere’s article:

Though he has 170,000 donors, many of the people who show up for Yang in person are younger, disaffected men—the kind who may seem like they’re looking for a way out of work, or those who attack politics with destructive detachment. I asked Yang what he would say to the people who would look at those supporters—and at Yang himself—and say that they need to just “grow up.”

“I mean, if you think about it, why are we trapped in this subsistence labor model?” he replied. “Why is it that a job is 9 to 5 or 10 to 6? And my wife’s work [stay-at-home mom] is not a job ... Ninety-four percent of the new jobs created in the U.S. are gig, temporary, or contractor jobs at this point, and we still just pretend it’s the ’70s, where it’s like, ‘You’re going to work for a company, you’re going to get benefits, you’re going to be able to retire, even though we’ve totally eviscerated any retirement benefits, but somehow you’re going to retire,’” Yang said. “Young people look up at this and be like, ‘This does not seem to work.’ And we’re like, ‘Oh, it’s all right.’ It’s not all right. We do have to grow up. I couldn’t agree more.”

Yang is unencumbered by the experience of actually trying to accomplish something politically.

It is also obvious to me that Andrew Yang’s confident, common-sense “fixer” approach to government is made possible by the fact that he has never worked in government, and has never had to actually test out any of his ideas. He appeals to those who are generally cynical about politics, because it is possible to say with Yang that we haven’t necessarily tried his way before. Though Yang himself does not spend too much time bashing government (at least on my reading, though I’ll be honest…I haven’t watched hundreds of hours of tape on the guy), his candidacy is fueled by the familiar notion that government isn’t doing what it should be doing because (insert reductionistic explanation here…the Swamp, “special interests,” etc.).

Instead, I’ve found that if “obvious” things haven’t happened yet in our politics, the reason for that is typically deeply entrenched in the political system, and there is often a good reason for it. Right now, Yang’s record in politics is basically a list of policy proposals, but while those policy proposals stand alone now, as president they would very much be in competition with one another. Yang has never had to compromise on his policies, or take contradictory stances, or flip-flop or do any of the other things that bug people about politicians because he’s never taken on the responsibility of a politician.

No one is attacking him yet.

This leads me to the final reason why Yang has support: no one really cares about him yet enough to oppose him. He hasn’t really been attacked by anyone, and especially not his Democratic primary opponents. What happens when people point out that his Freedom Dividend might actually be regressive, particularly since those who receive public benefits like food stamps will have to choose between their check from the government or their benefits—a choice that those who do not need public benefits will not need to make. And is a political novice really the appropriate successor for Donald Trump? Will Andrew Yang really restore America’s credibility around the world?

These are questions few really care to ask so far, which makes sense. Yang has never come close to breaking into the top-tier. He’s not exactly a bomb-thrower himself, though if you want proof that he’s not taken seriously enough to come under real scrutiny consider that his quote here on Trump’s weight has been barely covered, not to mention that it has not appeared on the front-page of any newspaper. In September, however, when a dozen candidates or former candidates will fail to make the debate stage—governors and Members of Congress included among them—Yang will be there. There are reasons for that, and the other candidates should not underestimate their power.

A few final notes:

-I am a big fan of Yang’s idea of “human-centered capitalism,” and believe it is a politically-astute way to get at the burgeoning critiques of capitalism coming from the left and the right. It reminds me of Bill Clinton/Obama economic advisor Gene Sperling’s recent work on “Economic Dignity,” which I discussed with Gene on The Church Politics Podcast.

-Yang might not have a great chance to win the nomination, but his campaign should be absolutely pilfered for lessons from candidates with more standing. I’ve tried to highlight here some of the aspects of his campaign that are most promising, but there are others.

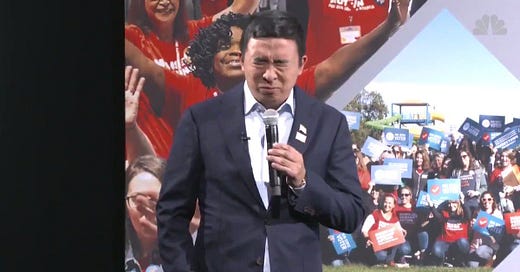

-This scene of Andrew Yang crying after being asked a question from a mother who lost a child to gun violence is deeply moving: