What a night we had on Super Tuesday. We feel pretty good about our predictions and analysis ahead of Super Tuesday. We told you Biden would shock America…he did. We told you he’d win Texas by 5-7…he did. We told you he’d win by 20+ in Virginia…he did. Minnesota, Massachusetts…we called em. We even said he’d get 28+ in California, and though the total vote isn’t in yet, it looks like he just might hit that benchmark as well.

We won’t get it right all the time, but it feels good when we do. Hopefully, you felt like because you get this newsletter, you were in the know, too!

In this post, I want to provide some analysis on why Biden did so well, acknowledge some real advantages Sanders has moving forward, discuss Warren dropping out and answer your questions.

Let’s dive in.

Why did Biden win Super Tuesday?

There are many reasons Joe Biden performed so well on Super Tuesday. I wrote about some of them in the last couple of posts, and others are so obvious that they aren’t worth going into too extensively here. I want to pull out one idea that I’ve been holding onto for a while, and which some folks have started to partially touch on just today.

One aspect of the deep, stark party polarization we see today, something that has been cultivated by extremists and now has backfired (as these kinds of efforts to channel hatred and antagonism tend to go), is that it provokes not just antipathy toward and ignorance about the “enemy” (Republicans, if you’re a Democrat), it also strengthens and essentializes one’s identity as a Democrat. We’ve seen this play out in this primary. Candidates like Kamala Harris, Julian Castro and Elizabeth Warren have paid for launching attacks against their opponents that turned progressive standards inward. To be blunt about it, Democratic voters are happy to cheer when Republicans are accused of being racist, sexist, corporatist, etc., because it is not just an attack against the “other side,” but an affirmation that they, as Democrats, are on the “right side.” More on this below…

The main point I want to make here is that following Buttigieg and Klobuchar dropping out, Biden was essentially running against three candidates who contested Democrats’ self-conception in vital ways. It’s a disaster for the general election to not be able to distinguish between Donald Trump and George W. Bush, as Bernie and many of his supporters seem unwilling or unable to do. It’s a disaster in a primary to compare Trump, Bush and Reagan with Clinton and Obama, and basically suggest the last forty years has been ruled by one ideology that you are contesting. That’s news to Democratic primary voters, who thought this whole time they were Democrats in rejection of Republicans. On Super Tuesday, Biden won not because people followed the marching orders of the establishment, but because of the message the consolidation sent around Biden to voters who go to politics looking for the community and affirmation that the Democratic Party offers to them. And when they looked at their other options: Bernie, whose very status as an independent is a challenge to Democrats’ self-conception; Bloomberg, who voted for George W. Bush and became a Democrat just recently; and Warren…who we’ll discuss now.

Warren’s Candidacy

Senator Elizabeth Warren ran a strong campaign. Even now, she’s in the high double-digits in national polls. She was excellent in debates. She drove the conversation for much of 2019 with her policy proposals. So why did she lose?

First, just to build off the main idea of the last section, she challenged Democrats’ self-conception in a way that was threatening. This was perhaps best exemplified by her suggestion Joe Biden was running in the wrong party’s primary. The Biden campaign wisely capitalized on the claim.

Second, there are advantages and disadvantages to running for president as a woman, particularly as a Democrat. The advantages are probably less worth talking about until, well, a woman can actually take advantage of them enough to win the presidency (I think there’s an argument to be made, for instance, that Hillary Clinton’s gender helped her in the Democratic primary to clear the field in 2016…only Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley were willing to put themselves in a position where they could be blamed for stopping history from being made. But, of course, if we are to acknowledge gender helped her get the nomination, we must acknowledge AT LEAST that it did not help her enough to win the presidency.).

The disadvantages are difficult to quantify except by the blunt and irrefutable number of zero, the number of women who have been elected president in this country. I don’t agree with Rebecca Traister’s writing on this topic all of the time, but she’s brilliant and convincing, and she’s changed my mind and made me look at things differently quite often. This essay of hers on the sort of double-bind female candidates are in is a good example of that. I’m interested in Warren sharing more of her perspective, as she promised to do today, and I don’t think these dynamics should be underplayed, nor used to sweep away any other failures of the Warren campaign.

Third, as has been shown today, Warren campaigned with a unique sense of calling, purpose and sense of righteousness. She was utterly convincing in her values-based approach to her campaign. If you run like that, it does put extra attention on changes, and she made three critical ones: 1) Her change on Medicare for All, which both undercut confidence in her policy acumen, her reliability and her authenticity 2) Her decision to go on the offensive against her opponents after insisting, so powerfully, that she was just not someone who thought about politics in those kinds of strategic terms 3) The Super PAC flip, which was truly difficult to justify given her previous comments on the subject.

Fourth, as I’ve written before, I was really high on Warren’s campaign when she announced, and through much of 2019 had told reporters and others not to underestimate her. I believed her clear commitment to the economic security of working families could win back the Rust Belt. Unfortunately, she lost that focus as we got into the last half, and especially the last quarter, of 2019. This is important: Warren’s closing message that she was the unity candidate was not a message about her ability to unite moderate and progressive wings of the party, as many interpreted it. Instead, it was the argument that she would unite the far-left that was motivated by structural economic concerns with the far-left that was motivated by issues like abortion, LGBTQ rights and other issues. Then, in the South Carolina debate in particular, she over-invested in using Mike Bloomberg as a foil, so that her economic case (which I believe is truly rooted in a deep concern for working families) became conflated with a sort of personal antagonism toward those who are wealthy.

Fifth, like several other Democratic presidential campaigns in 2020 and 2016, Warren’s campaign failed to see value in Warren’s more conservative instincts. When asked why she was a Republican for so long, Warren would say that it was because she was politically disinterested all that time. I doubt that’s the full story, and it would have been nice and an asset to hear what aspects of Republicanism in the 80s and 90s she found attractive, even if she’s changed her mind about those things. Similarly, Warren’s work on the “two-income trap,” which revealed some more traditional intuitions, or at least inclusive thinking toward those with more traditional intuitions, was something the Warren campaign seemed to avoid.

Sixth, readers of this newsletter know that I think 2020 has been about a move in voters’ views of authenticity from one that relies less on performance and more on history. Warren, as she emphasized, has not been in public life for long. The average voter did not know her well, if at all. Biden and Sanders have persevered in large part because of this.

Seventh, Amy Klobuchar’s presence in the race prevented women’s groups like EMILY’s List from endorsing Warren (though, Klobuchar could certainly argue that Warren prevented those groups from endorsing her).

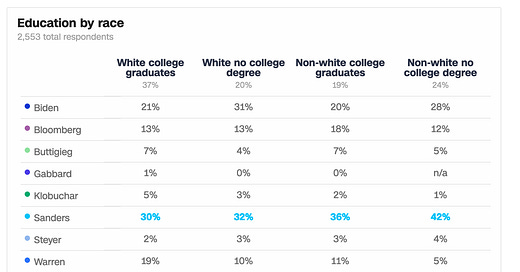

Finally, look, the clearest reason why Elizabeth Warren had to drop out is in the exit polls. When you go outside of Twitter and academic settings, her support was not sweeping…it was limited and narrow. I have to say, the extent to which some folks seem willing to go to avoid an analysis of reality, and instead pathologize voters who did not support their candidate, is embarrassing. You get the sense from some people that they thought their support for Warren was a favor they were doing for somebody else, only to find that the “somebody else” didn’t view their politics as heroic as they had hoped. It has been a real problem with a certain brand of progressivism to have utter confidence that you know what is best for people, especially “certain kinds” of people. It’s one thing to vote purely on self-interest. It’s another thing to pose as if you’re voting for someone else only to learn that “someone else” used their voice differently than you did. Particularly when we have data on this…people have actually voted. Look at these exit polls for the most concrete sense of why Warren lost:

California:

Texas:

Nevada:

In state after state, Elizabeth Warren performed best among white people with advanced degrees. Now, those folks count, too. If you desire, you could argue that she performed better with voters who were paying the most attention to policy proposals. Warren performed best among folks with advanced degrees, so the more educated you are, the more likely you are to support Warren. That’s not a bad thing. For academics and those who are deeply embedded in progressive discourse, Warren’s loss felt like a personal rejection. You see people trying to grapple with how voters didn’t see what was so clear to them about Warren’s candidacy. She was clearly the most capable, the most qualified. “As soon as more people hear what she’s saying, everyone will support her just like those who sit on editorial boards already do,” some seemed to think.

Yet, her campaign for the working class wasn’t supported by the working class. Her campaign and some of her supporters seemed to confuse the views of entire demographics with the perspectives of a few columnists, advocacy groups and Twitter personalities. Instead of explaining away this disconnect, perhaps it should provide an occasion for self-reflection in the days ahead.

This Race is not Over

Biden had a great night. He is a frontrunner, and in my view, he is the frontrunner. But this race is not over. Here are a few factors to watch in the next couple of weeks:

1) The Sanders’ campaign has floated that they’ll perform better among black voters outside of the South, and there’s some evidence this is a real possibility. I think this is particularly possible in the Rust Belt. While Biden won the black vote in South Carolina by 44 points, in Virginia by 52 points, in North Carolina by 45 points, and in Alabama by 62 points. In California, he won the black vote by 22 points, in Nevada by 10 points and in Minnesota by 4 points.

2) Does Bernie’s advantage with the Hispanic vote persist? It’s important to note that, like the black vote for Biden, Bernie hasn’t won the Hispanic vote by such a large margin everywhere. In fact, Biden won the Hispanic vote in North Carolina, for instance. Again, the Faith 2020 podcast episode with Rev. Gabriel Salguero prepared us well for this.

3) As I wrote before Super Tuesday, Biden basically caught Bernie defenseless after South Carolina. No debates. A wave of earned media. Bernie’s now able to pivot to focus on Biden exclusively. And he’s done this before. He’s going to apply the lessons he thinks he learned from 2016.

Your Questions

Basically, if no one gets a majority (1,991) of pledged delegates on the first ballot, then the superdelegates (there are 770 of them) are allowed to jump in on a second ballot and have their say. Delegates pledged to other candidates can side with a different candidate, too, so campaigns will lobby delegates to jump ship and support their campaign. The convention decides when a majority of delegates support one candidate.

I can’t tell you how unlikely this would be, and it became a lot more unlikely over the last week.

She did! But she didn’t because she knows both Biden and Sanders are going to leave certain key players in the party unsatisfied in a way she thinks she could avoid.

There will be much more time to write on this, but the Catholic vote is going to go a long way toward determining the general election, and it could be absolutely key in some of these upcoming states (Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania). Smart question from Guthrie.

1) It relies on treating voters like they’re idiots and misleading them. This should be made clear.

2) Would be worthwhile to explore the potential for ensuring this backfires with senior citizens.

Way too early to talk about VP, as we need to see how long it takes to get a nominee (remember: Biden is in a very strong position, but he hasn’t won yet. Talk to me after Florida.), what the state of the party is at that point, and how polling looks after the nominee is clear.

For Sanders, I’m convinced he’ll go with an unconventional pick: think, for instance, a union leader, or an innovative, progressive mayor (no, not Buttigieg).

For Biden, here are some names to throw in the hat: Amy Klobuchar (who I’m certain would have been his nominee in 2016), Stacey Abrams, Cedric Richmond, Mitch Landrieu, Jeanne Shaheen, Sherrod Brown, Bob Casey and Gretchen Whitmer.

I don’t think this would make sense this time around. No president wants to be forced to make governing commitments so heavily influenced by political considerations, unless absolutely necessary. In a general, there’s no need to make an additional stability/vision case against Trump. It’s self-evident with Biden.

Again, though, let’s be careful about calling the race over just yet.

Won’t answer this question fully here, though I do have thoughts! These thoughts would be much better informed if the exit polls had asked one helpful religious question, and it is absolute malpractice that this was not the case. I hope we’ll see some reporting that uncovers why this was the case very soon.

Will anyone provide cover—real, substantial cover—and commitments for a nominee who does?

The long primary allows for candidates to be vetted. Now, I kind of wish they couldn’t start campaigning until October, but we would lose quite a bit if, say, the nominee was effectively chosen over the course of just a couple weeks. Remember, by the end of March, probably about 70% of delegates will have been chosen, and voting just started in February. What I think would strengthen the process would be for campaigning to start later so that there wasn’t a full year of only advocacy groups and special interests paying attention, dragging the candidates out in front of them and forcing them to take positions that aren’t helpful…but, of course, party elites love that that’s how it works.

We really loved this question. I think what we’re already seeing is our politics is becoming less defined by the big government vs. small government debate that really drove our politics since the Reagan era. Both Trump and Sanders are evidence of this. Yet, what we should also learn from the Reagan era is that voters’ commitments are often not to a particular ideology, but to a kind of mood and a set of concerns that influence our politics but can also change and transform over time. I want to dismiss the notion of “wait till these kids actually have to pay taxes” kind of rhetoric. I also want to allow for the fact that people do grow and change.

Let me answer a little more concretely: Bernie has already changed the Democratic Party and our politics, but we should be careful not to anticipate that a) 18-30 voters’ politics will not change b) most importantly, that the next generation of voters after gen Z will necessarily share their politics.

Michael

P.S. If this work is valuable to you, would you consider becoming a subscriber?