If you’re a listener of Wear We Are, you heard us reference my argument regarding TikTok and Millennial and Gen Z information consumption. I thought I’d write it up.

It was supposed to be that isolated, closed-loop communities breed misinformation. We call them “old wives’ tales,” because the information they convey is retrograde and superstitious. Exposure to the broader world ought to be enough to cure those misunderstandings and delusions.

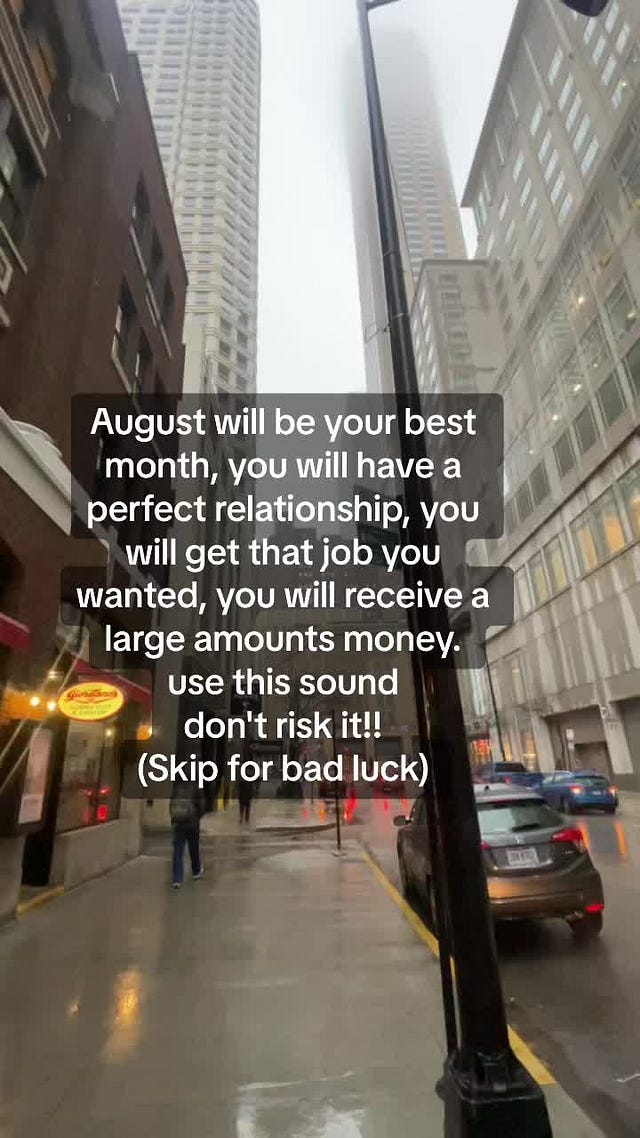

The internet promised to cure ignorance, though it became clear early on it would take a few generations. We had to wait for the digital natives, because Boomers were sending chain mail warning that “If you don’t send this to 13 people on your list, you’ll have bad luck for 3 years.” Parents and grandparents would discuss the snippets of local TV news coverage or recall the details of a spam email, and much of what developed was not so distant from old wives’ tales and the superstitions of locals in an isolated village. From faddish health tips to fear-driven crime coverage on local news, real-life decisions were made from the way this kind of information developed and spread.

Michael remembers being flustered as a boy when his mother was very upset that he was watching a cartoon — Rugrats. She couldn’t believe that trash was on their television and made him turn it off. It turned out she had heard from somewhere about a crass, vulgar animated show that was the rage among young boys. That show, of course, wasn’t Rugrats, but Southpark. Details, details.

More seriously, the sensationalism of local TV news coverage contributed to an environment of fear around things like child kidnappings. “It’s 11 o’clock. Do you know where your child is?” The rise of the helicopter parent is not removed from these dynamics.

And to be completely clear, local TV news is a good institution. When we don’t have much binding communities together, it’s there. We need it. But it also plays host to all kinds of stories that fuel misinterpretation for the sake of viewership. When I think of virality on the internet, I think of the viral local news stories that came before social media and are still used as TV’s form of clickbait today.

Between early internet misinformation, and a misinterpretation of local news, a refining process was necessary. We had to assimilate to the Age of Information.

Surely digital natives, those who grew up with the internet, are now applying the tremendous resources available to them in order to make the most realistic, evidence-based assessment of all things related to their life and outlook. Right? Surely!

Let’s peer in on TikTok and see what we find:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Look familiar?!

Here’s the thing, the channels and modes of communication are different, but the human behavior is the same for Millennials and Gen Z. For all our hubris about how we’re “breaking generational cycles,” lots of our behaviors look similar. It is not just political disinformation that has been empowered by social media, but the same kinds of populist lifestyle gossip that is mocked so readily in popular culture. Seriously, these TikToks are indistinguishable from the Nigerian prince who got your uncle to share his social security number.

It’s absolutely fascinating to watch this same dynamic play out for two generations that still consume their news from traditional outlets like a local TV station, but also heavily (91 percent!) from social media. The exorbitant amount of TikToks I receive on my algorithm-generated “For You Page” about various fads, trends, or alarming news are astounding. TikToks that are concerned about how we’re not seeing a certain piece of news in the mainstream media. Or how the government is trying to cover up a story. Or how we’re all living in a simulation and many are reporting their own experiences of “jumping timelines” or discovering a “glitch in the matrix.” Or the seemingly more innocuous TikToks such as the benefits of magnesium supplements for an array of health concerns, or what’s now being called the “gut health girlies” (female TikTok creators who are now major “influencers” concerning probiotics and gut health), or the craze about “slugging” (i.e. a skincare routine where you essentially coat your face in vaseline each night for better skin and anti-aging effects).

And medical TikTok writ-large has folks self-diagnosing all kinds of issues. It’s true, some folks have inadequate healthcare or physicians who aren’t listening to them, but I’d love to see interviews of doctors and nurses to ask them if they’re busy diagnosing the latest syndrome on TikTok or not. I now know so much about Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a group of connective tissue disorders (grateful to know!), but according to the comments on numerous videos, are there really that many people who have a rare syndrome? We don’t know yet.

These all ring like the local TV news stories that we know are still part of the local broadcasting repertoire, but reimagined for generations who may be watching local TV news and consuming TikTok.

Some of this simply feels like a sociological observation and nothing more. Humans are quirky! But here are a few of my concerns.

First, we know that these TikToks can gain millions of views and thousands of comments. Local news has never seen numbers like that, unless we are talking about a blooper that’s been passed around on YouTube. The potential, as so many experts have pointed out in all kinds of essays and news stories, is for embedding misinformation and disinformation into the minds of folks who have the power to continue to perpetuate those ideas and narratives over and over again.

Second, the algorithm. The algorithm figures out very quickly what makes you not just like or share, but what you pause on or re-watch 14 times as you read the comments. The algorithm knows these fads and trends are huge. It’s reading us like a book. Setting aside the idea that the Chinese government has access to this data (I will not go into the complicated aspects of that issue), computer algorithms are learning this human behavior, this seemingly human need for stories and narratives about “cool” or “hip” or “alarming” or “subversive” things. With the advent of ChatGPT and other super-sophisticated AI, we may have less and less control in the future over what we think is cool or alarming or what we should be writing our local council member about. Maybe AI will take this data and turn it into something harmless or helpful. Maybe not. We don’t know yet.

Finally, there is this false notion I sense from TikTokers that we are far more discerning than we might actually be. That we can handle all this information that the algorithm throws at us. I like to think that. But when presented with an Ehlers-Danlos TikTok, sometimes I do look to see if my skin stretches more than I thought it did. I know I don’t have the syndrome. I know I’m professionally trained to take lots of disparate information and pull together what is true, what might be true, what might not be true, and what is patently false and weave together an analysis. But goodness, TikTok and that algorithm are powerful forces for putting some doubt or an idea into my brain.

TikTok has the power to make generations feel like they’re not like Boomers or others before them, but that hubris only carries if we couldn’t see clearly the same behavior being repeated in 2023. Millennials and Gen Z love a good sensational story just as much as previous generations. The reach and penetration of those stories, however, is what makes them more concerning. It goes outside of what was formerly the local news bubble. It’s at a time of lightning-fast AI development. It’s something to watch.